They say necessity is the mother of invention, and for WMAs facing mounting challenges with limited resources, getting inventive was not a choice; it was a necessity. At Honeyguide, we never set out to become “innovators.” We simply needed to solve problems quickly while helping WMAs do more with less. Crops were being destroyed, rangers were under-resourced, and existing solutions were either too slow, too costly or simply out of reach. Communities needed real solutions, and when none came, we built them together.

Our innovation journey did not start in a lab. It started in the field, where things were broken, urgent, and real.

That urgency was the seed for our innovation department, but what has made it thrive is something deeper. We are not inventing for the sake of it. We are reimagining conservation through bold innovation and collaboration with our communities. We are listening closely to what communities want and need. There is no handover with us. Communities lead the process from day one. Together, we co-develop solutions, test them rigorously, and scale the ones that work. Our focus is not just on meeting immediate needs, but on identifying solutions with the potential to scale across landscapes. Because not everything that is sustainable is scalable. And in conservation, both are essential.

Our approach to innovation is cost-conscious by design. We are not just chasing gadgets or quick fixes. Innovation, for us, is not about being clever. It is about being useful, practical, and ready to replicate. It does not always mean new technology. Sometimes, it is about applying a familiar idea in a smarter way. The most impactful solutions are often the simplest, shaped by context, grounded in trust, and built to last.

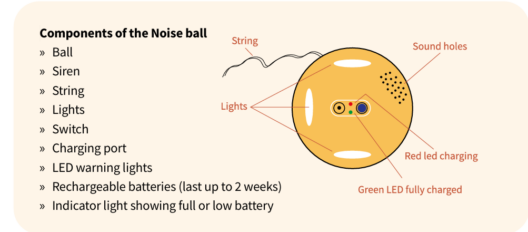

Noise Ball: Innovation Meets Urgency

When elephants destroy farms, they leave more than broken fences. They leave fear, anger, and loss. People lose harvests, income, and sometimes their lives. When communities in northern Tanzania turned to Honeyguide for help, we listened. If we believe in coexistence, we cannot stay silent when it costs people everything.

Together, we built the noise ball, an affordable, locally made tool to safely keep elephants out of farms and protect what matters most. It may not look like much, but the Noise Ball has changed the conversation around crop protection. Built with community input and designed for repeated use, it is both effective and affordable, costing under $45 per unit and requiring no infrastructure or ongoing maintenance. Unlike electric fences or commercial deterrents, it puts a reliable, practical solution directly in the hands of the people who need it most.

What makes the Noise Ball powerful is not just its price or portability, it is how it shifts the balance of power. Farmers who once relied on luck or dangerous methods like firecrackers or stones now have a repeatable, humane tool that works. With each deployment, fear is replaced with agency.

We have also seen that the psychological effect matters. When people feel they have a reliable response to elephants, the tone of the human-wildlife relationship changes. Farmers are less likely to retaliate. Rangers are less likely to be called in late at night. Tension gives way to trust.

The Noise Ball works by targeting elephants’ senses: sharp sound and bursts of flashing light disrupt their approach, forcing a retreat without harm. In 2024, we distributed over 200 units in conflict-prone areas, with over 95% success in deterring elephants.

But getting there was anything but smooth. The first prototypes were crude, bulky chicken-wire frames that were too heavy to throw unless you had Olympic-level strength and easily caught on branches, stopping the ball from rolling and blunting its impact. We kept at it, redesigning and testing alongside community members until the tool became what it needed to be: field-ready, practical, and durable.

That journey also led us to develop a systematic approach, combining field trials, behavioral observation, and data analysis, to understand where and how the Noise Ball worked best. We found it outperformed other deterrents like chili crackers and Mzinga Thunder Flashes, both in reliability and safety.

What emerged is not just a product, but a solution, a humane, cost-conscious tool that communities use with confidence. Made with them, tested with them, and now protecting the fragile balance of coexistence, its success is measured not by how loud it is, but by what it saves: crops, lives, and the trust between people and wildlife.

Source: Human-Elephant Conflict Handbook

Scaling What Works

This is no longer just a Tanzanian story. What began as a homegrown response to a local crisis is now being scaled across borders. The Noise Ball, and the broader Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC) toolkit behind it, is changing the way communities, rangers, and conservation organizations across southern Africa approach human-wildlife conflict. Because when something works, word spreads.

Scaling is not automatic. Many innovations in conservation fail to leave the pilot phase because they are too expensive, too complicated, or too tied to the organization that created them. Honeyguide’s approach is different. Every tool is built for handover. Every idea is documented, demonstrated, and stripped to what is essential. This makes them easier to adapt—not just copy—for new contexts.

In 2023, Honeyguide was invited by the Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC) to Namibia to introduce our low-cost, community-driven HEC innovations. Over several days, we exchanged ideas, explored how our innovations could fit Namibia’s context, and laid the groundwork for collaboration. Later that year, IRDNC and Namibian community rangers visited Tanzania to see the Honeyguide toolkit in action. Highlights from both exchanges are captured in this short video:

So when IRDNC learned that Honeyguide had developed a new HEC tool with a 98% success rate in reducing crop destruction, they knew they had to try it. In 2024, they reached out again, this time to bring the Noise Ball to Namibia. Their previous efforts using electric fences and community patrols were no longer enough. Human-elephant conflict was rising, and communities needed something more effective. Honeyguide’s HEC team returned to Namibia to train rangers and farmers on how to use and maintain the Noise Ball. The impact on the ground was immediate and significant.

“The Noise Ball has been a very useful tool for us. It works far better than the blow horn. With the horn, elephants always try to locate the sound before reacting, which can put people at risk. But with the Noise Ball, the flashing lights and loud noise confuse and irritate them, so they retreat immediately, making it safer for both people and elephants.”

— Gerson Muzuma, Kunene Elephant Ranger Coordinator, IRDNC

By 2025, the impact of Honeyguide’s innovation model had caught the attention of conservation leaders in Zambia and Zimbabwe. After reading our newly published HEC guidebook, teams from the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) reached out. They wanted to know whether these simple, proven tools, designed for affordability and built with communities, could support their own coexistence strategies.

After spending three days in the field with the Honeyguide team and WMA communities in Randilen and Mamire in northern Tanzania, the decision was clear:

“Thank you for introducing us to the HEC toolkit. It has been exciting to see how communities use these tools in the field. The innovation behind the Noise Ball is especially impressive, and we look forward to scaling it, along with other HEC solutions you have developed, across our own landscapes. As part of our coexistence efforts in IFAW’s Room to Roam landscapes, we plan to purchase Noise Balls for pilot use in Zambia and Zimbabwe. This is a remarkable example of community-centered innovation.”

— Simbarashe Chiseva, Community Development Officer, IFAW Global Programs, Zimbabwe

This is what real scaling looks like: tools born out of necessity, shaped through community partnership, and now making an impact across borders. These innovations are not flashy or imported. They are built with the people who use them, proven where it matters, and designed to grow. They are not just holding up, they are driving change at scale.

In southern Africa, what drew partners to the toolkit was not the technology, but the proof. A consistent 95–98% success rate. Tools used daily by communities. And a process that did not require importing parts or bringing in foreign consultants. These were solutions that could belong to them.

Kirikuu: The $10,000 Game Changer

In conservation, mobility is non-negotiable. Rangers must patrol vast areas, respond to threats, and navigate rough terrain. However, for most WMAs, the cost of reliable 4×4 vehicles, especially the industry-standard Land Cruiser, is simply out of reach. One vehicle can cost up to $80,000, draining budgets meant for much more than just transport.

This is where Kirikuu comes in.

Built in Honeyguide’s own workshop, Kirikuu is a modified Suzuki Carry 4×4 that does 80% of what a Land Cruiser can, for just $10,000. This one shift has made a big difference: more vehicles in the field, more funds available for protection and livelihoods, and far less dependency on external donors to fund protection budgets.

Kirikuu is not just a vehicle; it is a locally built, cost-effective conservation tool that delivers real performance in the field. It puts more rangers on the ground, strengthens local capacity, and reduces dependence on expensive, donor-funded imports.

Traditional vehicle procurement often involves multi-month grant applications, import logistics, and costly upkeep. Kirikuu cuts through that. Vehicles are built using locally sourced materials and existing chassis, reducing maintenance delays and ensuring parts are easy to replace. This means WMAs are no longer sidelined by broken trucks or empty garages; they stay on the move. In many cases, Kirikuu vehicles have doubled the patrol frequency of ranger teams and improved their ability to respond to incidents within hours instead of days.

Kirikuu is more than a budget solution. It is a rethink of how conservation logistics can work in tough environments. In 2024, we expanded the Kirikuu Vehicle Modification Project to upgrade five vehicles, adapting each to the real-world needs of rangers. Using custom modifications like enhanced suspension, bigger tires for off-road handling, added seating, and built-in storage for tools and gear, we tailored each vehicle to the challenges of WMA terrain.

This is not about cutting corners; it is about building smarter. Kirikuu proves that innovation does not need to be high-tech to be high-impact. These vehicles have increased patrol coverage, improved ranger response times, and allowed WMAs to operate with fewer delays and lower maintenance costs. And because they are designed, built, and maintained by people who understand the job, WMAs gain not just transport, but independence.

Kirikuu is more than a vehicle. It is a mindset shift, from dependency to practical, locally driven solutions. And like many of Honeyguide’s best ideas, it started with a simple question: What if we could just build our own?

Ranger Posts: Reinventing the Basics

Not every innovation needs to be shiny or new. Sometimes, it is about taking what already exists and building it better, faster, and smarter. That is what we did with ranger posts.

Traditionally, constructing ranger posts is slow, costly, and heavily outsourced. By the time a post is finished, it has already eaten into budgets meant for rations, patrols, or basic gear. So we changed the model.

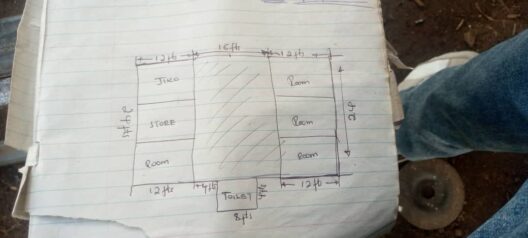

At the Honeyguide workshop, we completely re-engineered the process. We designed simpler, more durable structures using local materials, and built everything in-house. With input from rangers and communities, we focused on what mattered: faster construction, lower costs, and functionality in the field. Each post was then transported and installed in WMAs, complete with solar power and water systems.

Each build took about two weeks in the workshop, followed by three weeks on site. Because the units are largely prefabricated, it is easier and cheaper to build even in remote areas, requiring fewer people on site for fewer days than conventional brick buildings.

So far, we have built and fully installed five ranger posts across five WMAs in southern Tanzania, all operational and actively supporting protection efforts. These are not just buildings—they are strategic tools. Built faster, for less, and designed to boost ranger morale and field coverage where it matters most.

We also made intentional design changes based on ranger feedback. Each post includes multiple sleeping rooms, a dedicated kitchen (jiko), a store for secure equipment storage, and an indoor toilet, all within the same structure for ease and safety. The posts are spacious enough to house up to 10 rangers comfortably and include a mess area with a television; simple features that help boost morale and foster team cohesion. Solar setups provide power for radios and charging lights. These are small, thoughtful details that make a big operational difference, allowing rangers to stay in the field longer, work more efficiently, and rest with dignity.

By building these in-house, we cut costs by nearly 40% compared to outsourced construction, allowing limited budgets to stretch further without sacrificing quality. It also gives us the flexibility to solve design problems quickly, test new ideas, and improve the process in real time.

The impact is real. Rangers now have reliable shelter, power, and access to clean water in the areas they patrol. Morale has improved, response times have shortened, and coverage has expanded. Communities, too, see the posts as visible proof that protection is working and that it is built with their needs in mind.

Sometimes, a smarter way of doing something simple can unlock the biggest gains. Ranger posts are not just structures. They are strategic tools for stronger protection.

Let Us Not Wait for Perfect

Innovation in conservation does not need to be complex or expensive. It can begin with a simple question asked in the right place. It can be built in a small workshop, field-tested by rangers, and adapted by farmers. What matters is that it works: reliably, affordably, and in the hands of those who live with the stakes every day.

From the Noise Ball to Kirikuu to modular ranger posts, these are not pilot projects or unproven concepts. They are tools that solve real problems, designed for scale and born from necessity. Their success is not theoretical; it is happening now. In Tanzania. In Namibia. Soon, in Zambia.

Community-led innovation is not charity. It is strategy. WMAs are not passive recipients of external help. They are builders, testers, and decision-makers. When solutions are created with them—not for them—they scale not because of donor push, but because of local pull. Because they already fit the context. If conservation is to last, it must be rooted in what communities can own and sustain. That is not a future we are imagining. That is work already underway.

Innovation should not sit on the sidelines, waiting for perfect conditions or perfect technology. It should start right here, with people, with potential, and with what works. We do not need more moonshots in the conservation sector. We need smart, adaptable tools in the right hands. And we need to make sure every idea is measured not by how novel it sounds, but by how far it goes and how many people it serves.

Honeyguide’s approach works because it is built on real needs, shaped by community insight, and tested for cost, scalability, and impact. We do not build in isolation. We build with people, and for people.

So let us stop waiting for the perfect idea. Let us build the right ones. Let us scale what works. Let us start here.

Photo Credits: Monica Dalmasso/Jamal Fadhili